The discovery of microplastics in human placentas has sent shockwaves through the scientific community and raised urgent questions about our daily consumption habits - particularly regarding bottled water. Researchers first identified these plastic particles in placental tissue in 2020, and subsequent studies have only deepened concerns about what this means for fetal development and human health.

Microplastics - defined as plastic particles smaller than 5mm - have now been found in every environmental niche scientists have examined, from the deepest ocean trenches to the highest mountain peaks. Their presence in human reproductive organs represents a disturbing new frontier in plastic pollution research. The placenta, long considered a protective barrier for developing fetuses, appears permeable to these microscopic invaders.

Italian scientists made the initial breakthrough when they analyzed six placentas from healthy pregnancies and found microplastics in four of them. Using Raman microspectroscopy, they identified particles as small as 5 microns (about the size of a human red blood cell) from at least four different types of plastic. Most concerning was the location of these particles - on both the fetal and maternal sides of the placenta, and even within the membrane that surrounds the fetus.

Subsequent research has painted an even grimmer picture. A 2023 study published in Environment International examined 62 placental samples and found microplastics in every single one. The average concentration was 2.1 micrograms per gram of tissue - equivalent to about 1000 particles per placenta. Polyethylene, used in plastic bags and bottles, accounted for over half of the detected particles.

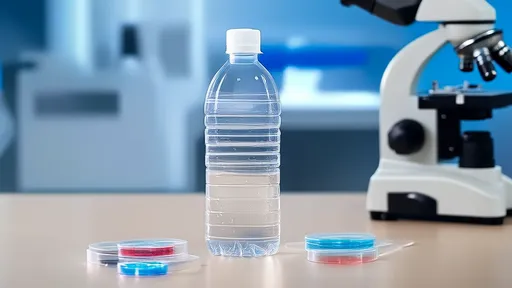

This raises inevitable questions about bottled water, which numerous studies have identified as a significant source of microplastic ingestion. A 2018 investigation found that 93% of bottled water samples from 11 major brands contained microplastics, with concentrations averaging 325 particles per liter - double the amount found in tap water. More recent analyses suggest the actual numbers may be far higher when accounting for smaller nanoparticles.

The plastic contamination occurs through multiple pathways. Some particles come from the packaging itself - polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles shed microscopic fragments, especially when exposed to heat or sunlight. Others originate from the bottling process or even the source water. Single-use plastic bottles have been shown to release increasing amounts of microplastics as they age, meaning that bottled water sitting on store shelves or in warehouses continues degrading into smaller particles.

Health researchers are particularly concerned about the additives in these plastics. Many microplastics carry chemical contaminants like phthalates (plastic softeners) and bisphenol A (BPA), which are known endocrine disruptors. When these particles accumulate in placental tissue, they may interfere with crucial developmental processes. Animal studies have shown that microplastics can cross the blood-brain barrier and potentially affect cognitive development.

Dr. Sarah Thompson, an environmental health researcher at King's College London, explains: "The placenta is supposed to be this incredible filtration system that protects the fetus from harmful substances. Finding microplastics there suggests our bodies are being infiltrated by pollution at the most fundamental biological levels." Her team's work indicates that inhaled and ingested microplastics can travel through the bloodstream and accumulate in organs.

The implications for bottled water consumption are profound. While scientists can't yet definitively prove that microplastics cause specific health problems, the precautionary principle suggests limiting exposure where possible. Pregnant women may want to be especially cautious, given the potential for developmental impacts. Switching to filtered tap water in glass or stainless steel containers could significantly reduce microplastic intake.

Water industry representatives argue that bottled water remains safer than many alternatives in areas with poor tap water quality. The International Bottled Water Association points out that microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and that their members adhere to strict safety standards. However, critics note that current regulations don't address microplastic contamination specifically, and testing methods remain inconsistent.

Emerging research suggests the problem may be worse than we imagined. Advanced imaging techniques have revealed that what initially appeared as individual microplastic particles are often actually clusters of thousands of nanoplastics - particles smaller than 1 micron. These tiny fragments may be more biologically active and more likely to penetrate cells. A single liter of bottled water could contain hundreds of thousands of these invisible plastic fragments.

The solution isn't as simple as switching to alternative packaging either. Aluminum cans often have plastic liners, and even cardboard cartons contain plastic layers. Glass bottles, while plastic-free, are heavier and more energy-intensive to transport. Some companies are developing plant-based bioplastics, but these currently represent a tiny fraction of the market and may present their own environmental challenges.

Public health experts emphasize that while individual choices matter, systemic change is needed. Plastic production has grown exponentially in recent decades, with millions of tons entering the environment annually. Even if we stopped all plastic production tomorrow, existing waste would continue breaking down into microplastics for centuries. Some nations have begun implementing microplastic filtration requirements for wastewater treatment plants, but such measures are costly and not yet widespread.

For consumers concerned about microplastics in bottled water, scientists recommend several practical steps: First, avoid reusing plastic bottles, as wear and tear increases microplastic shedding. Second, store bottles away from heat and sunlight, which accelerate plastic degradation. Third, consider investing in a high-quality water filter certified to remove microplastics if relying on tap water. Reverse osmosis systems appear particularly effective, though more research is needed.

The discovery of microplastics in human placentas serves as a sobering reminder of how thoroughly plastic pollution has penetrated our world. As research continues to uncover potential health impacts, the bottled water industry faces increasing scrutiny. While absolute avoidance of microplastics may be impossible in our modern environment, informed choices can significantly reduce our exposure - and perhaps protect the most vulnerable among us, including developing fetuses, from potential harm.

What remains clear is that the microplastic problem extends far beyond bottled water. These particles are in our food, our air, and now our very bodies. The placental findings represent both a scientific breakthrough and a societal wake-up call, challenging us to reconsider humanity's relationship with plastic at the most fundamental level. As the research evolves, so too must our understanding of what constitutes true water purity in the age of microplastic pollution.

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025